Tax planning is largely shaped by a comparison of your current tax situation to your future expected tax situation and timing your income and deductions to minimize your tax liability. In an election year, an additional variable takes heightened importance; the prospect of a change in the tax law. At the time of this writing, the makeup of the U.S. Senate and hence future tax laws are uncertain. For purposes of the ideas expressed herein, we have assumed that the current tax law will remain in place for the foreseeable future.

Manage Tax Brackets

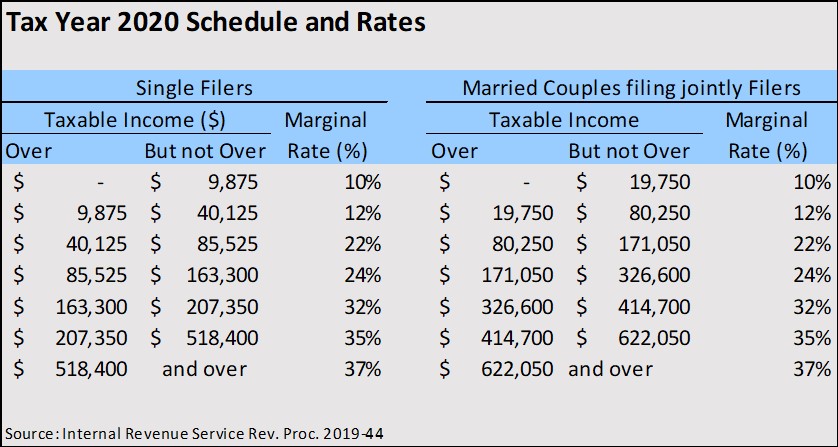

One of the most important aspects of minimizing income taxes is understanding and, to the extent possible, managing your marginal tax rate. Below is the 2020 tax rate schedule for a single person and a married couple. Let’s assume that a married couple, Harry and Sally, have had a challenging year financially in 2020 and their taxable income is expected to be $150,000 compared to the $350,000 that it has been in the past and is expected to be in 2021 and beyond. This level of taxable income puts Harry and Sally in the 22% tax bracket in 2020 and the 32% tax bracket in 2021. In such a circumstance Harry and Sally will generally want to defer tax deductions to 2021 when they will be more beneficial. A $10,000 deduction in 2021 will be worth $1,000 more in 2021 than in 2020. Conversely, they would prefer to recognize additional income in 2020 than in 2021. The opposite would be true if Harry and Sally’s expected income in 2020 and 2021 were reversed.

Let’s examine some of the ways that Harry and Sally can shift their income or deductions from one year to another to manage their tax bracket as their circumstances change. They can:

Change their elective deferrals to employer retirement plans and IRAs. The amounts of the contributions can be adjusted, and they can choose between pre-tax and after tax (Roth) contributions.

Delay or accelerate their charitable contributions.

Delay or accelerate the payment of state estimated income tax payments and property taxes.

If self-employed, accelerate business income or delay business deductions.

Take distributions from retirement plans that are not otherwise required.

Convert all or a portion of a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA.

Accelerate or defer capital gains and losses from the sale of financial assets.

Another reason to proactively shift income and deductions is to take advantage of the many tax breaks that are limited based on your income. Here is a list of some of the most common:

American Opportunity Tax Credit – up to $2,500 Federal tax credit per child for those who have paid college education expenses and with income below $180,000.

The COVID stimulus check – up to $2,400 Federal tax credit if your income is below $198,000.

Child Tax Credit – up to $500 Federal tax credit per child if your income is below $400,000.

Roth IRA contributions – up to $7,000 deduction per person if your income is below $206,000.

The above list is not all inclusive and is based on the income limits for a married couple. The amounts differ for those not married and filing a joint return.

Maximize Charitable Deductions

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) expanded the standard deduction and capped the deduction for state taxes to $10,000. As a result of these changes many people that had previously itemized their deductions are now claiming the standard deduction. As a reminder, the standard deduction is the amount that you may deduct from your income regardless of the eligible itemized deductions you have actually paid.

These new rules have caused many to lose the tax benefit of their charitable contributions. For those impacted, the loss of the charitable deduction can be limited by bunching charitable deductions into a single year. Consider the following example:

Harry and Sally Jones paid $75,000 of state income and property taxes. This deduction is limited to $10,000. They have no mortgage and they gift $30,000 annually to charity. Using the typical direct annual gift approach, the Jones’ would elect to itemize their deductions because their itemized deductions of $40,000 exceed the $24,400 standard deduction for a married couple. Over a four-year period, the Jones’ would have deducted a total of $160,000 using the direct annual gift approach. Alternatively, if the Jones’ pay the next four years of their charitable giving in year one their total allowable deductions over the four-year period would be $203,200. This is a $43,200 increase in deductions merely by changing the timing of the payment!

For those that prefer to make charitable gifts annually, it is possible to both get the tax deduction in one year and distribute the funds to charity in the future. This can be accomplished by funding a charitable entity called a Donor Advised Fund (DAF). Making charitable donations with highly appreciated stock remains a very effective way to make your donations whether they are made directly on an annual basis or through a donor advised fund.

For those over age 70 ½, up to $100,000 per year of required individual retirement plan distributions can be directed to charity. In the above example, let’s assume that Harry and Sally are over age 70 ½ and are required to take significant IRA distributions. In lieu of giving $30,000 annually to charity from their non-retirement funds, they may designate $30,000 per year of their required IRA distribution to charity (a qualified charitable distribution (QCD)). By taking this approach their total deductions over the four-year period would be $217,600; a $57,600 increase from the direct annual gift approach merely by changing the source of funds for the charitable gifts.

Save for Retirement

If the past is any indication, it is clear that no one can predict future income tax rates and policy. For those who are currently working and planning for the day when they will rely on their financial assets to maintain their lifestyle, one of the most important ways to plan for an uncertain future tax landscape is to accumulate wealth in a manner that provides for flexibility. The best way to obtain this flexibility is to accumulate wealth in all three forms: taxable accounts, tax free accounts and tax deferred accounts. By accumulating wealth in all three forms you have the flexibility to choose the source of your income in retirement and hence manage your income tax liability. In addition to mitigating taxes, managing your income in retirement can help you manage your Medicare premiums. Medicare premiums vary based on your income and can differ by as much as $4,100 each year.

Because it has only been available for a relatively short time, the after tax (Roth) portion of wealth accumulation is often where people fall short. For a married couple, Roth IRA contributions are not permitted if your adjusted gross income exceeds $206,000. For those that have income in excess of this amount there is a way to circumvent this limitation. There is no income limit for after-tax contributions to a traditional IRA and there are no income limits on converting a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA. As a result, contributions can be made to a traditional IRA on an after-tax basis and subsequently converted to a Roth IRA regardless of your level of income. In the financial planning community this strategy is referred to as the Backdoor Roth IRA and it has recently been recognized by the IRS. This can be a great way to add to the after-tax portion of your wealth over time.